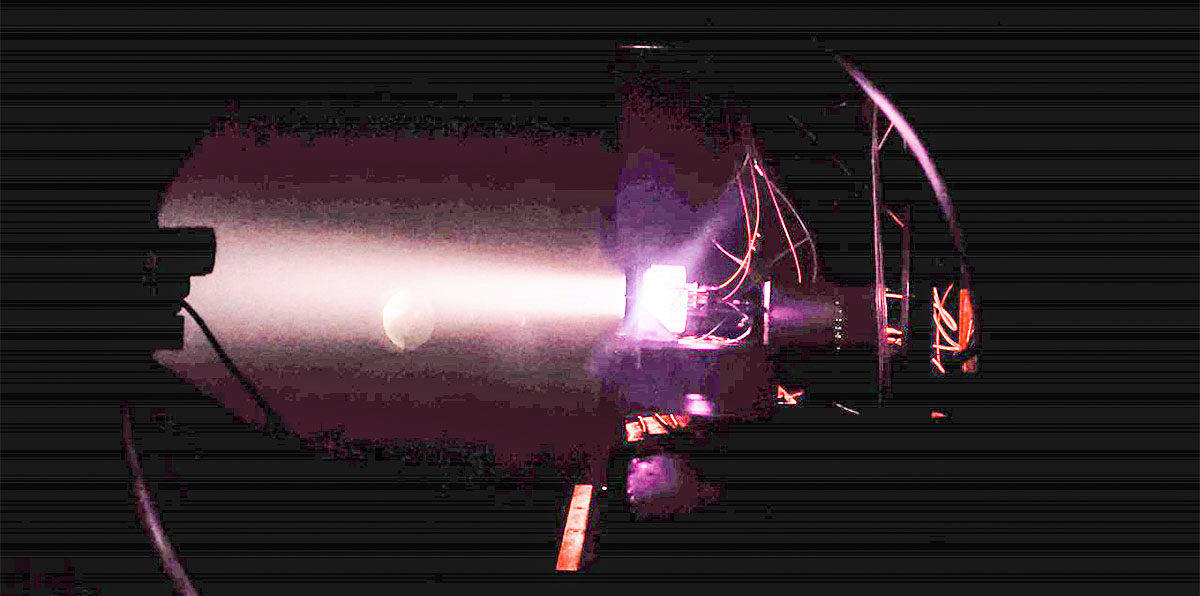

In the Fall of 2019, Aerospace Engineering School doctoral student David Jovel led the first-ever U.S. test of the Radiofrequency Ion Thruster (RIT-10) (above). "I was fortunate enough to get some nice data on its performance," says Jovel, a 2020 recipient of a Hispanic Scholarship Fund award.

|

|

|

The Hispanic Scholarship Fund has selected Daniel Guggenheim School of Aerospace Engineering doctoral student David Jovel to receive one of its 2020 scholarships.

Already a GEM Scholar, Jovel said the HSF support will allow him to meet a May 2022 graduation goal. If that date sounds far off to some, it fits perfectly into Jovel's big picture.

"I've always opted to take fewer courses than other PhD students because it's made me more available to help support other students," he says.

Jovel says mentoring others has been one of his most critical undertakings, but it's also a bit of a double-edged sword. On the one side, he is drawn to helping undergraduate students and his graduate peers slog through the coursework, quals, and research that can seem overwhelming to anyone, especially a first-generation scholar. But the other side of that sword is unquestionably sharp: mentorship sucks up time -- to read, to research, to network, to think.

Jovel doesn't fault any grad students for sticking strictly to their coursework and research, but, for him, supporting undergrad and incoming grad students was not up for debate.

"Part of the reason I came to graduate school later than most is because no one told me graduate school was really an option when I was younger. I didn't have a mentor. After I earned my undergraduate degree, I was working at the Aerospace Corporation where one of my colleagues literally said to me 'Hey, dude, I got a Ph.D. and it was awesome - best decision I ever made. It gives you a lot of freedom to work on the projects you find interesting. You can do it. You should do it.'"

Those words launched Jovel on a journey that continues to inspire his coursework, teaching, research, and mentoring at Tech. There's always too much to do, he admits, but being busy hasn't dampened the thrill of learning. Right now, his time is split between lab work and the literature review for his dissertation.

And he's on fire.

"It blows me away that I get to read some amazing research papers written long before I came along. Some of the papers, I'd read before, but it's amazing, as I read them again, now, I have new insight on what they were thinking and doing," he says.

"I have such deference for these researchers who came before me in my field. The knowledge and understanding they had are astounding when I think about how advances in technology have supported my owb work as a researcher today. Some of them were doing this work without all of the computers and great numerical methods we have now, and they were still pulling out great results. It makes me want to give it my best, just out of respect for their work."

Respecting a Legacy of Hard Work

Born in New York, David Jovel absorbed a strong work ethic from his parents, who immigrated to the United States from El Salvador. As a young man, his father had harbored ambitions of becoming an agricultural engineer, but when civil and political violence in his homeland forced him to move, those ambitions morphed into providing his family with opportunities for a better future in the United States.

"The thing is, he worked hard to provide us a safe and stable life, even after my mother died at a young age and we had to move to Texas," says Jovel. "I will always respect that."

During his high school years, David worked for three summers alongside his father, who drove a garbage truck. At the time, the elder Jovel was proud to bring his son to work, where many of his colleagues were, like he, immigrants. He thought it was an opportunity to build David's character and motivate him to work hard in school. Ultimately, he was right: that summer job convinced David to work hard, if only to respect his father's sacrifices.

But, at the time, a teenage David Jovel wasn't feeling it.

"I was well-paid and all, but I hated that job - it was so hot, humid, dirty, physically demanding, and all of my friends were at the beach or doing something fun," he recalls.

"But you know, years later, I was sitting in a lab struggling to understand this technical paper and it got me thinking back to those guys I worked with on that garbage truck - undocumented immigrants, just trying to get by. I was working hard trying to read that paper, but they were also working hard. If they'd seen me struggling, they would have been really proud of me and what I'd gone on to do. They would've smiled and told me to keep trying. I thought about that, and it motivated me to work even harder at understanding that paper."

Jovel is not entirely certain what his career will look like when he finishes his doctorate, but he's confident that, whatever it is, it will be an opportunity of his own making. He will return to Aerospace Corporation, of course, but, further down the road, he might want to teach at a college level. Or not. He pointed out that he gifted his master's degree to his father, who framed it and hung it in his living room. But his doctorate? That's all David's.

"I came here to get the credential - the Ph.D. - because I thought it would give me freedom to do interesting things. And it has."